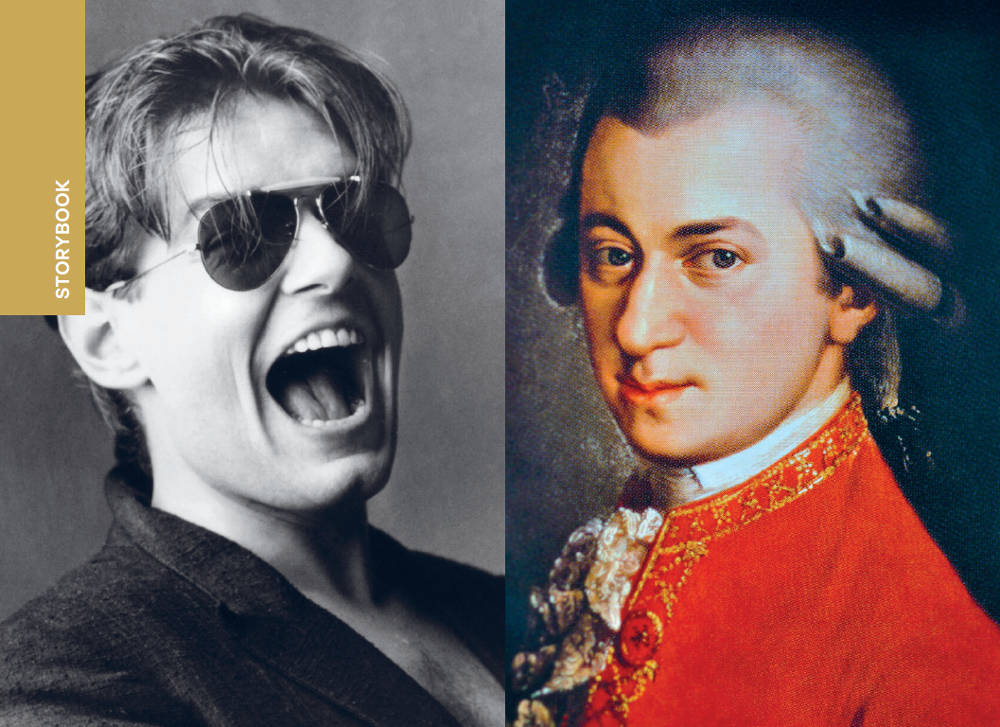

These two Austrian musical figures have more than a few things in common – and their legacies live on. By Anthony Haywood

Many thanks to Lonely Planet for permission to republish this essay from the upcoming Austria travel guide.

WHEN THE END came, it was sudden and made the headlines worldwide. He died too early, at the age of 40 years in 1998 – the Austrian rock musician Falco. Just over 200 years earlier, another famous Austrian composer, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, died at the even less timely age of 35. Falco. Mozart. Two very different people and lives, and yet it is difficult to imagine Austrian music today without them.

Falco – It Ended in a Wreck

If we can believe the portrayal in the film of his life, ‘Falco – Verdammt, wir leben noch!’ (Falco – Damn we’re still alive!), before colliding fatally with a bus in the Dominican Republic, he spent the last hour of his life alone inside his car in a disco car park.

From his modest beginnings as Hans Hölzel (his real name), growing up in Vienna’s 5th district of Margareten and starting his career in the oddly named Austropop rock-punk group Drahdiwaberl in the 1970s, Falco brought together the coolness of New Wave rock in the 1980s in songs that often switched back and forth effortlessly between German and English. Frequently, he delivered the lyrics in chants in the Viennese dialect and rather priggish English, earning the reputation of being the German-speaking world’s first rapper.

Although ‘The Kommissar’ was a hit in Europe, his big international breakthrough came with ‘Rock me Amadeus’, which topped the music singles charts in the UK, USA and elsewhere. Fatalism was always in there somewhere; drugs and alcohol often crept into his musical style. Legendary songs like ‘Ganz Wien’ (Total Vienna) about heroine abuse, ‘Jeanny’ and ‘Junge Römer’ (Young Romans) played with the chill of human life on the edge of a precipice.

On the Shoulders of Giants

Falco was a stroke of musical luck for contemporary Austria. Before he shook up the scene, you could be forgiven for feeling Austria was still slumped in the comfortable armchair of mid- and late-18th-century Vienna Classic, if briefly tickled out of it by the likes of Franz Liszt (1811–86), Johannes Brahms (1833–97) and Anton Bruckner (1824–96) in the 19th century.

The earliest of the great Austrian composers was Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), whose nickname was ‘Papa Haydn’. He earned the monikers ‘Father of the Symphony’ and ‘Father of the String Quartet’. Franz Schubert (1797–1828) followed and achieved fame composing vocal works, operas, chamber music and symphonies, above all his Symphony No 9 in C Major, which was first performed publicly only after his death. Something of a good socialiser, he was known for his ‘Schubertiades’, which were intimate house parties where guests gathered to hear his works. Although he was yet another Austrian musical great in a rush to his grave (only 31 when he died), his influence on classical music was enormous.

Less well-known is the ‘blind virtuoso’ Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759–1824), who received voice training from the Italian composer Antonio Salieri (1750–1825), and this is where the Mozart plot thickens: with the supposed rivalry between Salieri and the genius who inspired Falco’s biggest hit, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91).

Mozart & the ‘Poison’ Rumours

Mozart was born in Salzburg – among his sweetest local legacies are so-called ‘Mozart balls’ (Mozartkugeln) of chocolate, pistachio, marzipan and nougat – and began tinkling his way to fame at the age of four on the piano, earning a reputation as a Wunderkind. After Mozart’s meteoric rise, Salieri was appointed by the Habsburgs to head Italian opera at the royal court.

Rumours that Mozart was poisoned surfaced soon after he died. However, if this sounds like an envious court appointee slipping a shot of mercury to an adult Wunderkind with fame, fortune, looks to kill and a glamorous wife by his side, a dip into a 1983 article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine entitled ‘Mozart’s illness and death’ paints a very different picture.

The author describes Mozart as obsessed and immature, a child plagued by numerous illnesses, 5ft tall, disorganised and unable to make ends meet, suffering from melancholia, snubbed by the local aristocracy in Vienna after initial success, and so it goes on.

The things going for him were an enduring fondness for his wife and rather acute hearing. Not forgetting that he also happened to be a revolutionary genius in musical composition.

Mozart’s great works include Symphony No 40, The Magic Flute, Eine kleine Nachtmusik, Requiem and Piano Concerto No 21. Along with musical cousins such as Bach and Beethoven, he was a tour de force in Western classical music.

The poisoning rumour kept its traction when Alexander Pushkin wrote a play Mozart and Salieri (1830), and another Russian, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, wrote the opera Mozart et Salieri in 1898.

Fires were rekindled in 1980 when Peter Shaffer wrote the play Amadeus, which became the basis for Miloš Formann’s film of the same name in 1984. One year later, Falco burst through the doors pleading with Amadeus to rock us, in his glottal rap-like style, describing our Wunderkind as a drinking, indebted superstar. And indeed he was.

If you think maybe ‘the music died’ with Buddy Holly or Lynyrd Skynyrd in plane crashes, Prince with pills, Bowie or perhaps even Nipsey Hussle, it’s still alive with Mozart, and, in Austria especially, it has survived the bus crash that took Falco.

Thanks once again to Lonely Planet for permission to republish this essay from the upcoming Austria travel guide